An article under a headline: ”At Kosovo Monastery, Nationalist Clamor Disturbs the Peace”, published by “The New York Times” in mid of March 2021, is following:

At Kosovo Monastery, Nationalist Clamor Disturbs the Peace

The monastery’s Serbian Orthodox abbot says he is subject to “rabid nationalism” from all sides. His biggest headache: a land dispute with ethnic Albanians, whom he protected during the war in the 1990s.

By Andrew Higgins

Published March 13, 2021Updated March 16, 2021

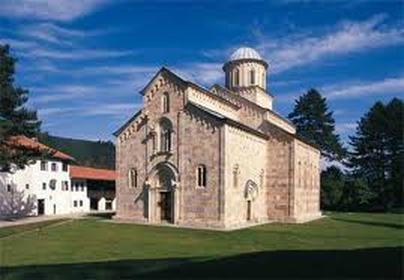

DECAN, Kosovo — Inside the walls of Father Sava Janjic’s 14th-century monastery reign silence and calm, interrupted by the occasional soft footfall of the few monks remaining in this revered outpost of the Serbian Orthodox Church in a hostile western Kosovo.

But outside the Visoki Decani Monastery, which is still protected by NATO troops more than two decades after war in the Balkans ended, is the persistent clamor of what Father Sava calls a “rabid nationalism” directed at him from all sides.

“This might be a sign that I am not wrong, that I am not on the bad side,” said the 56-year-old abbot, dressed in a long black cassock, standing near the altar of his monastery’s medieval stone church. “I’m now attacked by extremists on all sides.”

“This might be a sign that I am not wrong, that I am not on the bad side,” said the 56-year-old abbot, dressed in a long black cassock, standing near the altar of his monastery’s medieval stone church. “I’m now attacked by extremists on all sides.”

A longtime critic of the ethnic chauvinism that drove his former homeland of Yugoslavia into a frenzy of violence in the 1990s, Father Sava — whose father was a Serb and mother a Croat — has won few friends but gained many detractors in the Kosovo that emerged from that chaos.

He has been vilified as a traitor by ethnic Serbs who say he has supported the largely Muslim Albanians responsible for Kosovo’s break from Serbia in the 1990s. Vojislav Seselj, a former Serbian deputy prime minister and convicted war criminal, has denounced the abbot as a “notorious traitor.”

Father Sava has also been condemned by ethnic Albanians who resent him as an unwanted reminder of past Serb hegemony, even though the abbot sheltered many of them from the extremist Serb nationalists who wanted to kill them or drive them into exile during the war that erupted in Kosovo in the late 1990s.

And he has endured fierce criticism from all sides for his outspoken opposition to any redrawing of the map to partition Kosovo along ethnic lines.

Those attacks underline the intractability of the ethnic divide and hostility to those who seek to straddle it in Kosovo today, a state of affairs that Father Sava has for years railed against on social media, earning him the nickname “the cyber monk.”

The most pressing challenge he now faces comes from the ethnic Albanians who account for more than 90 percent of Kosovo’s population and have, through threats and occasional violence, purged the nearby town of Decan of a tiny Serb community over the past two decades.

The crux of that challenge today is land, the kind of issue that has divided communities in this region for generations.

A long legal battle being waged by Father Sava’s monastery to recover church land confiscated after World War II has been seized upon by Albanian nationalists as a land grab undertaken as part of a Serbian drive to regain control of Kosovo, which has been an independent state since 2008.

“They have too much land already — this land belongs to the people of Kosovo,” said Rajep Berishi, a 75-year-old ethnic Albanian, as he waited for a bus down the road from the monastery. “We hope the United States will close the monastery. We can’t close it. The monks are very powerful.”

In reality, a far more powerful force in this mountainous corner of Kosovo is Ramush Haradinaj, a former commander of the Kosovo Liberation Army, or K.L.A., the guerrilla force that led the battle against Serbian forces. A native of the area, he helped turn Decan, which Serbs call Decani, and surrounding villages into a guerrilla stronghold during the war.

Pictures of Mr. Haradinaj adorn billboards around the town. In the central square, next to a cultural center housing the offices of the K.L.A., disbanded as a fighting force but still a strong presence in many towns across Kosovo, stands a big sign: “I ❤ the K.L.A.”

The local mayor, Bashkim Ramosaj, an ally of Mr. Haradinaj, has resisted giving the monastery back any land, defying a 2016 ruling by Kosovo’s Constitutional Court that the territory claimed by Father Sava must be returned. The mayor, who declined to be interviewed, told local media outlets that he would rather go to jail than obey the ruling and surrender territory.

The land, 60 acres of farmland and forest outside the monastery walls, belonged to the church until 1946, when it was seized by Yugoslavia’s socialist government.

In the 1990s, the remnants of a crumbling Yugoslav state returned the land following the rise to power of Slobodan Milosevic, an atheist communist functionary who had metamorphosed into a champion of Serbian nationalism and the Serb Orthodox Church.

While the ethnic Albanians who took shelter in the monastery during the war quietly support the monks, the abbot said, their political leaders often view the land dispute “as a continuation of their war against Serbia, as if we are Milosevic proxies, which we are not.”

The court ruling that confirmed the monastery’s land claim, he added, “was not a Milosevic decision but a decision by the highest court of Kosovo.”

The foot-dragging on implementing the court’s ruling has increasingly exasperated the United States, which sent warplanes to attack Mr. Milosevic’s troops in Kosovo in 1999 and broke his grip on the territory.

The monastery’s case over its land, Philip S. Kosnett, the American ambassador, warned in a recent statement, “is not about ethnicity, politics, or religion; it is about property rights and respect for the law.”

The ambassador added, “This failure to adhere to the rule of law, extended over years by several different Kosovo governments, calls into question Kosovo’s commitment to equal justice.”

Albin Kurti, whose center-left political party won parliamentary elections on Feb. 14 and who is set to become Kosovo’s new prime minister, said “we will respect all decisions of the courts” but added that all sides needed to show “mutual understanding and sensitivity.”

Kosovo, he said, has no issue with Father Sava and other ethnic Serbs living on its territory, but only with the Serbian government in Belgrade, Serbia’s capital, which has refused to recognize his country’s independence.

Endrin Cacaj, a 25-year-old ethnic Albanian tech worker, echoed that view over coffee in a bar near the offices of the K.L.A. “We have no problem with the abbot personally,” he said. “But we all have a problem with these Serb institutions. They all follow orders from Belgrade and want our land.”

The church has had a hard time winning trust partly because of the role played by Orthodox priests during the wars of the 1990s, when some denounced Mr. Milosevic but others supported his land grabs in Bosnia and Croatia to create a “Greater Serbia.” Some churchmen blessed Serbian troops and even members of murderous paramilitary gangs.

Father Sava, complaining that Kosovo media regularly “vilified” the church, dismissed as a “blatant lie” accusations that Serbian priests in Kosovo had endorsed bloodshed, accusing ethnic Albanian politicians of “selling cheap nationalist stories for electoral reasons.”

Members of different ethnic communities, he said, often mix happily outside of Kosovo, but “here they cannot live normally because they have to enter into nationalist paradigms and are supposed to behave as proper Serbs or proper Albanians should behave.”

This, he said, “is not natural. People are supposed to live together regardless of their differences.”

Father Sava declined to say whether he accepts Kosovo’s independence but, while a citizen of Serbia, he carries an identity card issued by the Kosovo government, something that Serb nationalists cite as proof of treachery.

The abbot said he would not give up his fight, or his determination to condemn what he sees as wrongdoing on all sides, including by fellow Serbs.

When a group of ethnic Serbs loyal to Belgrade attacked the son of a Serb opposition politician in Kosovo with metal bars last month, he denounced the attackers on Facebook: “These people are not Serbs, they are inhuman.” He added: “When will we face our own demons and not just accuse others?”

Accusing others, however, is a deeply entrenched habit in a region where just about everyone has been a victim at one time or another.

Father Sava said his monastery has survived through centuries of Turkish rule, occupation by Italians and Germans during World War II, and the ethnic slaughter of the 1990s, and will again persist.

“If these walls could talk, they could tell you of much more turbulent times than now,” he said, pointing to the medieval frescoes that decorate the church.

“I am not planning to leave at all, as long as I am in this world. This is my home.”

Andrew Higgins is the bureau chief for East and Central Europe based in Warsaw. Previously a correspondent and bureau chief in Moscow for The Times, he was on the team awarded the 2017 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting, and led a team that won the same prize in 1999 while he was Moscow bureau chief for The Wall Street Journal.

A version of this article appears in print on March 14, 2021, Section A, Page 12 of the New York edition with the headline: Inside, a Sanctuary. Outside, the Roar of Kosovo’s Nationalists